re-thinking urban retail

The Design and Planning of "Dark Stores"

and Public Spaces,

Case Study: Manhattan, New York City

Juanita Halim

__________________________________________

MIT Master in City Planning Thesis 2023

![]()

The Design and Planning of "Dark Stores"

and Public Spaces,

Case Study: Manhattan, New York City

Juanita Halim

__________________________________________

MIT Master in City Planning Thesis 2023

Abstract

The retail industry has transformed into various formats due to the fast-paced social and sharing economy changes driven by technological advancements. The recent concept, grocery “dark stores” (retail facilities that are designed for online order fulfillment mostly located in urban areas), is expected to stay as e-commerce and omni-channel operators view them as cost-effective means of delivering quick services to customers. City officials are currently discussing the potential advantages and drawbacks of “dark stores” which could affect changes for street livability in the absence of retail storefronts. Should cities ban “dark stores” that compete with traditional brick-and-mortar retailers?

This thesis analyzes the proliferation of online grocery shopping and how “platform urbanism” (Sadowski, 2020), a novel set of digitally-enabled socio-technological assemblages rooted in the urban affects the spatial distribution of grocery “dark stores” activities by understanding their location and target customers. By using spatial analysis and interviews, this thesis tries to answer three questions: what is the role of grocery “dark stores” in cities?; where are they located?; and what are their impacts on the urban fabric? It uses NYC (Manhattan) 2021 decennial census and retail food stores data collected in 2022 and 2023 to provide some insights to these questions. The result shows that 1) The location of grocery “dark stores” are mostly located in neighborhood areas with high retail food stores and facility concentration 2) Grocery “dark stores” in Manhattan are located mostly in the Commercial and Manufacturing districts 3) Despite the rise of grocery “dark stores,” high funding from Venture Capitalists, and their promise of convenience to customers, in mid-2022, grocery “dark stores” in Manhattan faced exits due to dwindling investor funding, competitive market landscape, and political environment driven by Russia-backed Venture Capitalists.

In the digital era, strategies to digitally transform the city need to consider the implications of different types of retail formats and stakeholders involved. There is a need for urban policy and regulation to address how new retail platforms can reshape the nexus between businesses location, their design and function and the public. As this thesis shows, there is more urgency to do so as new form of retail and businesses are emerging as a result the tech-enabled digital economy and urban new urban infrastructure.

The retail industry has transformed into various formats due to the fast-paced social and sharing economy changes driven by technological advancements. The recent concept, grocery “dark stores” (retail facilities that are designed for online order fulfillment mostly located in urban areas), is expected to stay as e-commerce and omni-channel operators view them as cost-effective means of delivering quick services to customers. City officials are currently discussing the potential advantages and drawbacks of “dark stores” which could affect changes for street livability in the absence of retail storefronts. Should cities ban “dark stores” that compete with traditional brick-and-mortar retailers?

This thesis analyzes the proliferation of online grocery shopping and how “platform urbanism” (Sadowski, 2020), a novel set of digitally-enabled socio-technological assemblages rooted in the urban affects the spatial distribution of grocery “dark stores” activities by understanding their location and target customers. By using spatial analysis and interviews, this thesis tries to answer three questions: what is the role of grocery “dark stores” in cities?; where are they located?; and what are their impacts on the urban fabric? It uses NYC (Manhattan) 2021 decennial census and retail food stores data collected in 2022 and 2023 to provide some insights to these questions. The result shows that 1) The location of grocery “dark stores” are mostly located in neighborhood areas with high retail food stores and facility concentration 2) Grocery “dark stores” in Manhattan are located mostly in the Commercial and Manufacturing districts 3) Despite the rise of grocery “dark stores,” high funding from Venture Capitalists, and their promise of convenience to customers, in mid-2022, grocery “dark stores” in Manhattan faced exits due to dwindling investor funding, competitive market landscape, and political environment driven by Russia-backed Venture Capitalists.

In the digital era, strategies to digitally transform the city need to consider the implications of different types of retail formats and stakeholders involved. There is a need for urban policy and regulation to address how new retail platforms can reshape the nexus between businesses location, their design and function and the public. As this thesis shows, there is more urgency to do so as new form of retail and businesses are emerging as a result the tech-enabled digital economy and urban new urban infrastructure.

Grocery "Dark Store"

In the United States: With online grocery sales hitting $192B by 2025, we expect on-demand online grocery spend to hit a 15% share of that total, or about $28B in total. Dark Store is a grocery or retail store that is not opened to the public, used as a warehouse for quick-commerce deliveries - (McKinsey & Company, 2022. Grocery startups promising delivery in 15 minutes or less have cropped up in urban areas around the world, raising millions of dollars from investors and reshaping retail footprints in cities.

Their vision is to replace the local grocery store the way Uber disrupted car ownership. By turning groceries into something just at the end of your fingertips rather than something planned and scheduled, ultrafast services want to change how we shop entirely (Asplund, 2021). Grocery “dark stores”, through their 15-minute delivery services, change the way people grocery shop and the way economics work, influenced by urban density, proximity to order locations, and number of purchases (Wells, 2021). Arriving in every location within a city without planning or following proper zoning areas (Saltonstall, 2021), this thesis project aims to explore the impacts of online grocery shopping activities through grocery “dark stores” on the urban fabric, zoning, and land use. Therefore, relevant variables such as proximity to demographic characteristics, land use, and zoning will be analyzed to determine livable streets, neighborhoods, and communities within the presence of this new typology of retail space in cities.

In the United States: With online grocery sales hitting $192B by 2025, we expect on-demand online grocery spend to hit a 15% share of that total, or about $28B in total. Dark Store is a grocery or retail store that is not opened to the public, used as a warehouse for quick-commerce deliveries - (McKinsey & Company, 2022. Grocery startups promising delivery in 15 minutes or less have cropped up in urban areas around the world, raising millions of dollars from investors and reshaping retail footprints in cities.

Their vision is to replace the local grocery store the way Uber disrupted car ownership. By turning groceries into something just at the end of your fingertips rather than something planned and scheduled, ultrafast services want to change how we shop entirely (Asplund, 2021). Grocery “dark stores”, through their 15-minute delivery services, change the way people grocery shop and the way economics work, influenced by urban density, proximity to order locations, and number of purchases (Wells, 2021). Arriving in every location within a city without planning or following proper zoning areas (Saltonstall, 2021), this thesis project aims to explore the impacts of online grocery shopping activities through grocery “dark stores” on the urban fabric, zoning, and land use. Therefore, relevant variables such as proximity to demographic characteristics, land use, and zoning will be analyzed to determine livable streets, neighborhoods, and communities within the presence of this new typology of retail space in cities.

Methodology

This research employs both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The quantitative method relies on spatial and location analysis technique to understand the spatial configuration of “dark stores” as related to urban form and activities and their market competition. The spatial and location analysis method will take place through GIS to determine existing urban forms in the form of graphics representing the area under investigation.

Exploratory Findings

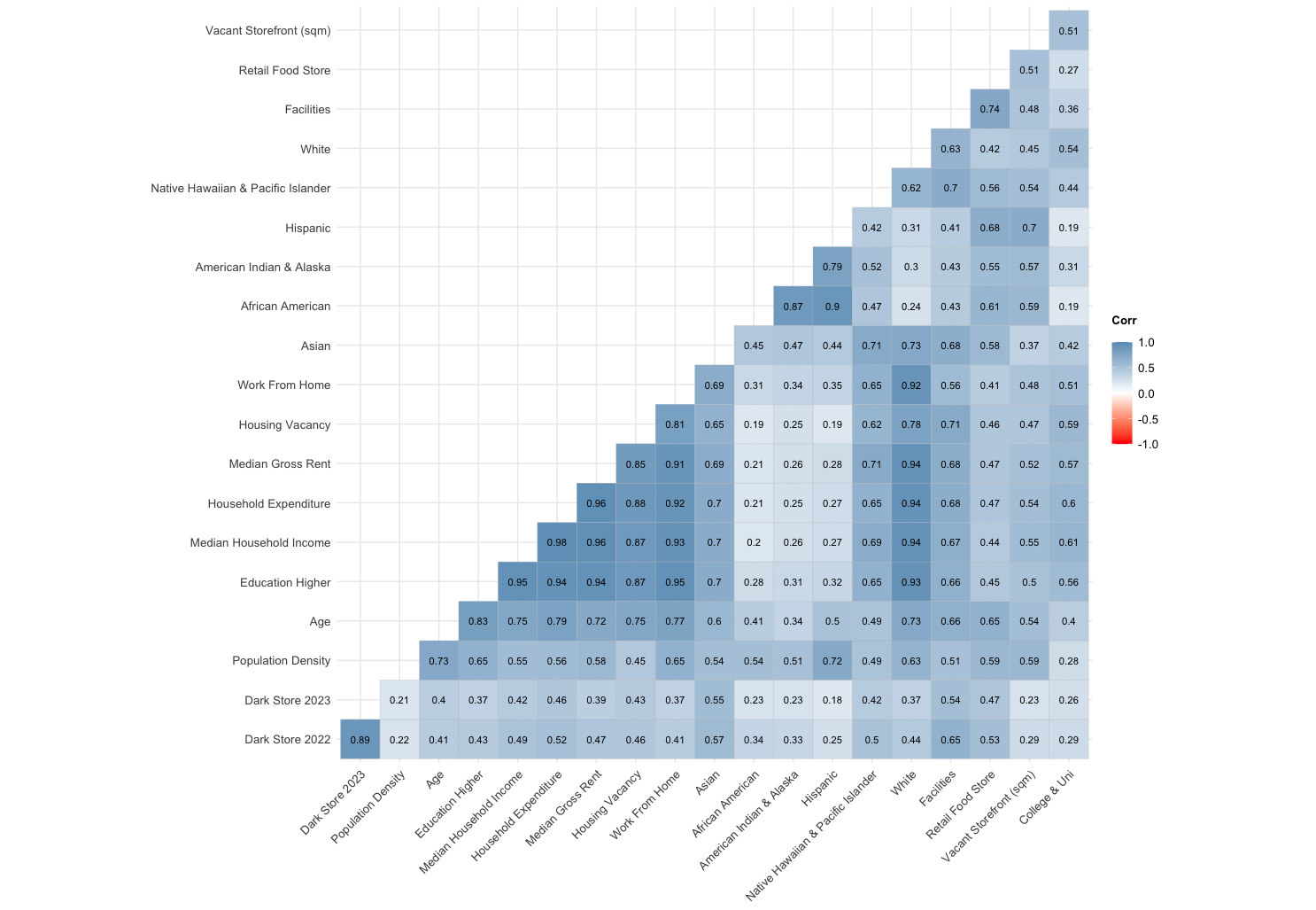

To begin, I checked the correlations between selected independent variables in the data and identified the correlation and statistical significance of the dependent variable based on each Neighborhood Tabulation Areas (NTAs). I did the former by running Spearman’s correlation test for non-normal distribution data type and correlation p-value test to determine the significance of the relationships using R.

In the correlation analysis, I observed a positive correlation between grocery “dark stores,” points of interest, and several demographic characteristics. This positive correlation is consistent in both 2022 and 2023, with facilities and retail food stores as “points of interest” having a higher correlation than “demographic characteristics.” On the other hand, some variables, such as population density, Hispanic, African American, American Indian and Alaska population, vacant storefronts, colleges, and university have low correlation. These relationships and findings strengthen the factors mentioned in the industry interview, suggesting the importance of density towards other retail food stores and service-oriented businesses or facilities to determine location selection.

In analyzing statistical significance, the p-values suggest that most of the correlations are significant at 0.05 level in both years. This means that the observed relationships between grocery “dark stores” and these variables are unlikely to have occurred by chance. However, it is important to note that correlation does not imply causation. While these correlation coefficients indicate the presence of relationships between grocery “dark stores” and the variable listed, they do not provide information about the direction or underlying causes of these relationships. Further analysis and research are necessary to understand the complex factors influencing grocery “dark stores” trends and their associations with the mentioned variables.

In the correlation analysis, I observed a positive correlation between grocery “dark stores,” points of interest, and several demographic characteristics. This positive correlation is consistent in both 2022 and 2023, with facilities and retail food stores as “points of interest” having a higher correlation than “demographic characteristics.” On the other hand, some variables, such as population density, Hispanic, African American, American Indian and Alaska population, vacant storefronts, colleges, and university have low correlation. These relationships and findings strengthen the factors mentioned in the industry interview, suggesting the importance of density towards other retail food stores and service-oriented businesses or facilities to determine location selection.

In analyzing statistical significance, the p-values suggest that most of the correlations are significant at 0.05 level in both years. This means that the observed relationships between grocery “dark stores” and these variables are unlikely to have occurred by chance. However, it is important to note that correlation does not imply causation. While these correlation coefficients indicate the presence of relationships between grocery “dark stores” and the variable listed, they do not provide information about the direction or underlying causes of these relationships. Further analysis and research are necessary to understand the complex factors influencing grocery “dark stores” trends and their associations with the mentioned variables.

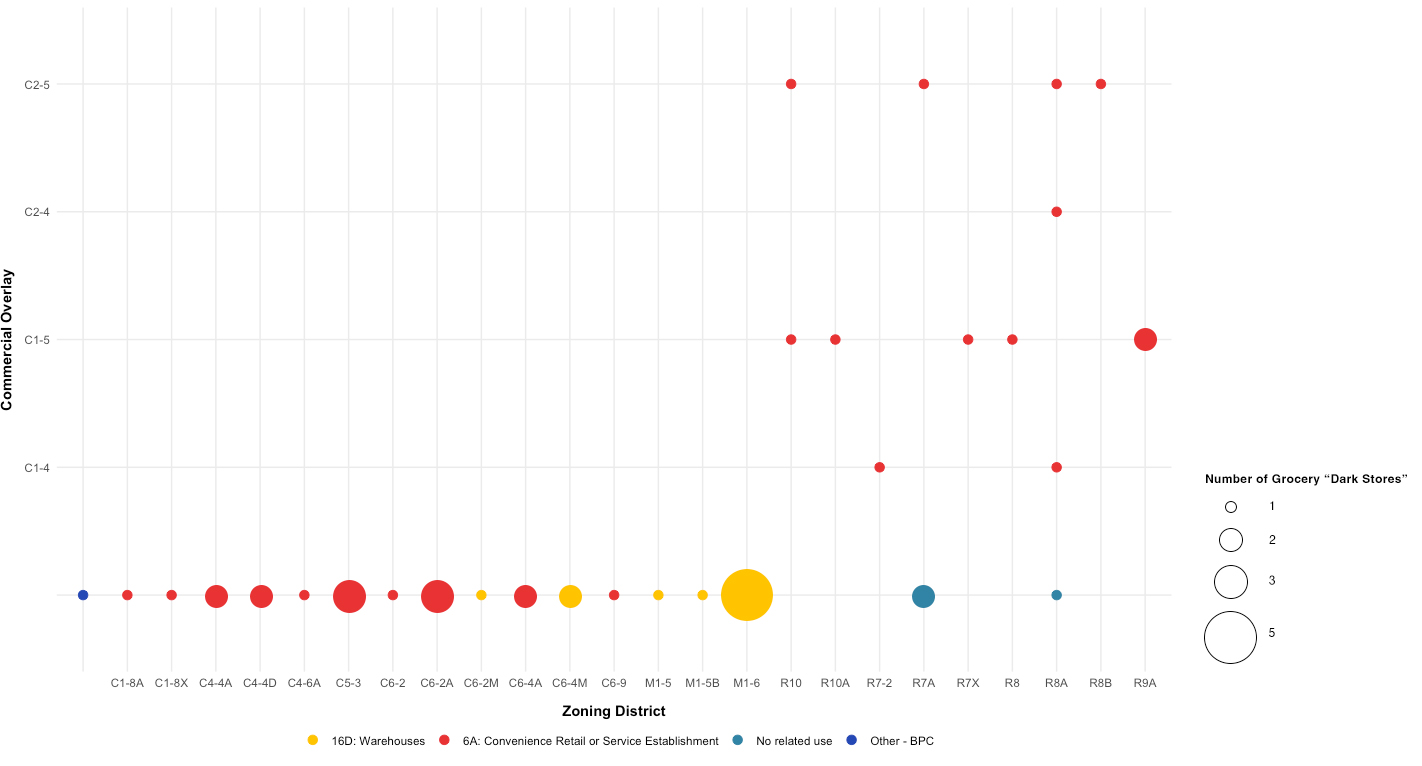

Potential of Zoning Violation: Warehouse or Grocery Store?

In April 2022, Council Member Gale Brewer did a sample survey of 26 grocery “dark stores” and put together an interactive map with the civic tech group Beta NYC (Figure 54) identifying the locations of these micro-fulfillment centers, which found 81 percent were operating outside the zoning designation permitting warehouse use. She says the “dark stores,” some of which have papered-over windows so passersby could not look in, compete with actual grocery stores and bodegas, and reduce foot traffic in retail corridors (Chadha & Garcia, 2022). Council Member Gale Brewer mentioned that from zoning perspective, the facilities operate in a gray area between commercial and industrial land use. For example, the GoPuff storefront on the Lower East Side is located in a residential zoning district and located in a mixed residential and commercial use building (Miao, 2022). Traditional fulfillment centers are typically categorized as warehouses which are zoned for manufacturing and some commercial districts.

![]()

![]()

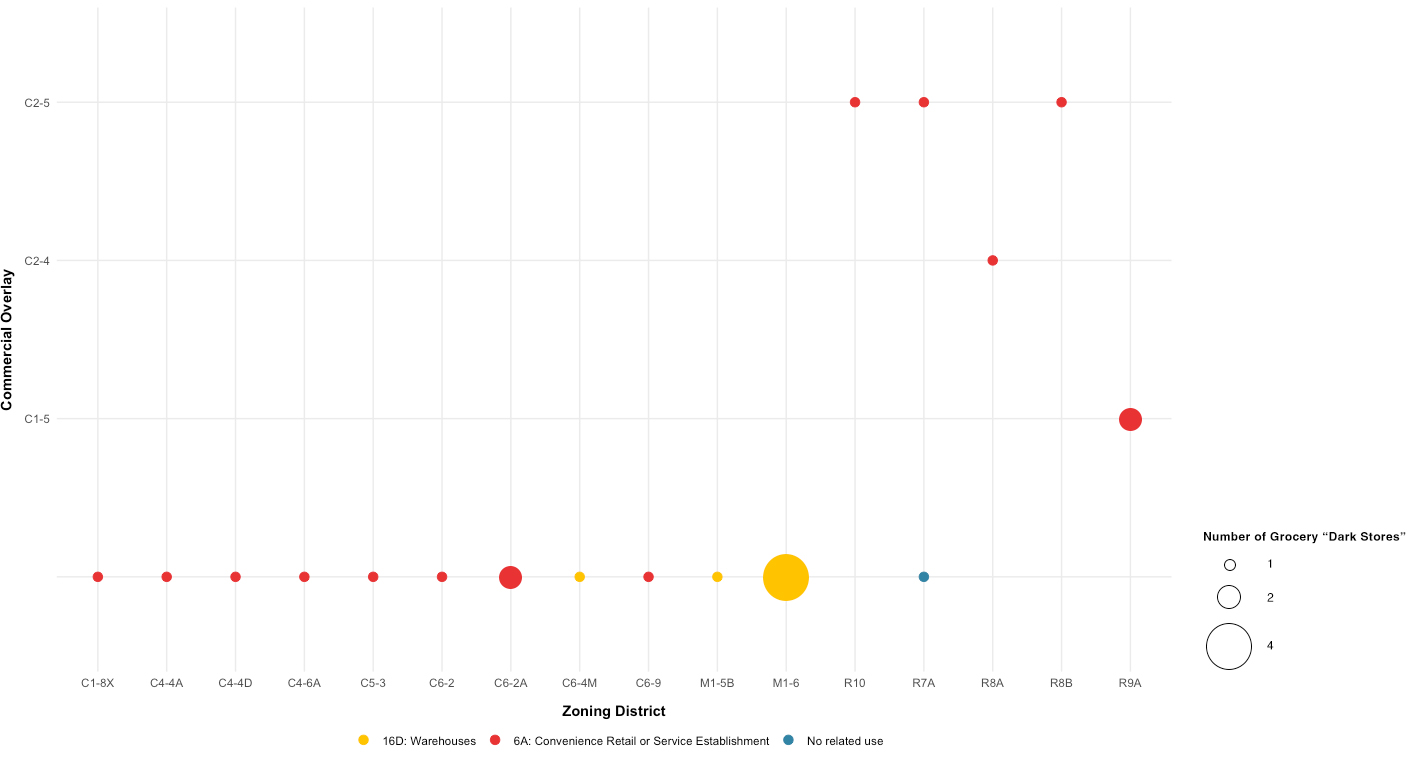

Looking at the distribution of grocery “dark stores” Use Code and Zoning District in 2022 and 2023, the analysis further indicates that these stores are primarily situated in Commercial and Residential Districts with Commercial overlays, aligning with the permitted uses in their respective zoning districts. However, it is important to acknowledge that there is still a small number of grocery “dark stores” that require further examination to ensure compliance with the zoning regulation. It is crucial to address these cases and ensure that all grocery “dark stores” fully comply with zoning and land-use regulations to maintain the integrity of urban fabric in Manhattan.

In addition to that, it is worth noting that grocery “dark stores” representatives have expressed a commitment to complying with local zoning and permitting obligations, including making adjustments to their operations to meet guidelines and exploring the transformation of stores into neighborhood amenities. Those guidelines include allowing customers to be admitted to a space and providing them a place to wait for their order to be prepared and delivered to them in person – readjusting their operations layout that will align with local guidelines. With ongoing efforts to address zoning and land-use concerns, there is a potential for these stores to evolve and better integrate into the urban fabric while meeting the needs of local communities.

Looking at the distribution of grocery “dark stores” Use Code and Zoning District in 2022 and 2023, the analysis further indicates that these stores are primarily situated in Commercial and Residential Districts with Commercial overlays, aligning with the permitted uses in their respective zoning districts. However, it is important to acknowledge that there is still a small number of grocery “dark stores” that require further examination to ensure compliance with the zoning regulation. It is crucial to address these cases and ensure that all grocery “dark stores” fully comply with zoning and land-use regulations to maintain the integrity of urban fabric in Manhattan.

In addition to that, it is worth noting that grocery “dark stores” representatives have expressed a commitment to complying with local zoning and permitting obligations, including making adjustments to their operations to meet guidelines and exploring the transformation of stores into neighborhood amenities. Those guidelines include allowing customers to be admitted to a space and providing them a place to wait for their order to be prepared and delivered to them in person – readjusting their operations layout that will align with local guidelines. With ongoing efforts to address zoning and land-use concerns, there is a potential for these stores to evolve and better integrate into the urban fabric while meeting the needs of local communities.

Will Grocery “Dark Stores” Phenomenon Stay?

Starting mid-2022 to 2023, the number of grocery “dark stores” in Manhattan was cut in half from 44 stores to 22 stores. Stores such as BUYK, Fridge No More, and JOKR were pulling out of cities or had filed for bankruptcy. Will these new evolutions and changes in grocery activities continue to stay?

From the findings, I found that changes to the number of grocery “dark stores” establishments per NTA vary from 33% to 100%. Their exits were influenced by the consolidation of the ultrafast delivery sector in the country as the space faced dwindling investor funding, a competitive economic environment, and political influence. For example, in an article by Grocery Dive, JOKR CEO, and cofounder Ralf Wenzel mentioned that the company decided to leave the United States to focus its resources on Latin America because the region is still underpenetrated and underserved. In addition, Fridge No More and BUYK shut down from the US market due to US Sanctions on Russia, as Russian investors backed both startups (Garber, 2022).

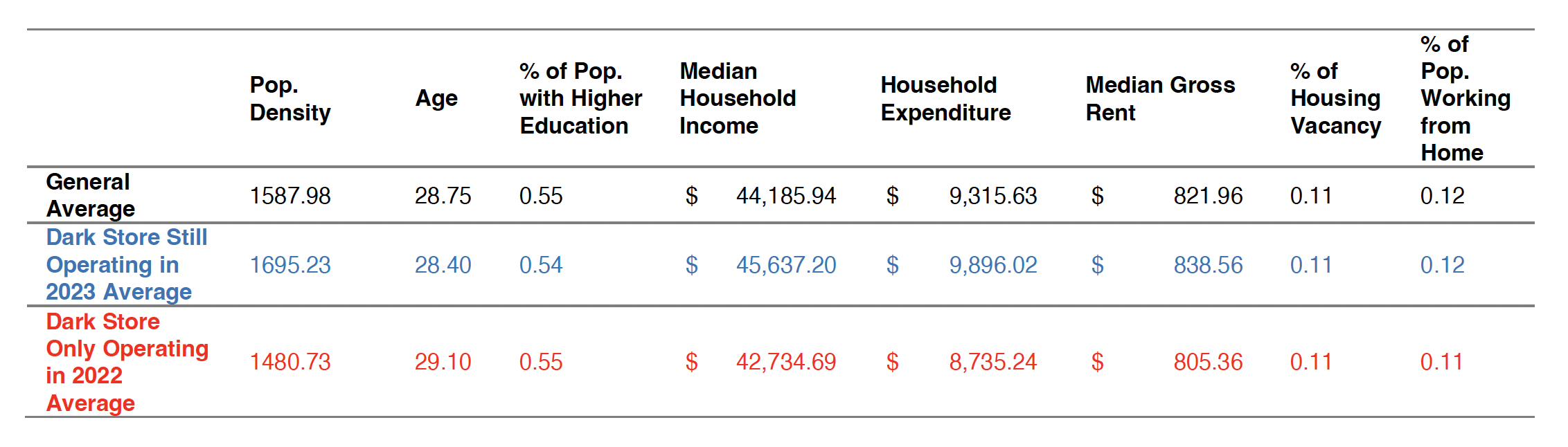

On average, grocery “dark stores” that survived the following year, although not significant, had higher potential in coming in the year 2022 and closer demographic characteristics than the general average (Table 15 and 16). In addition, the surviving stores had more extensive funding from Venture Capitalists: billions versus millions. Moreover, a surviving company such as GoPuff has been around in the United States since 2013, steadily progressing and expanding its operations and technology platform. GoPuff CEO Yakir Gola mentioned that it is indeed a complex business to scale; for example, to expand their service line to include alcohol, the process takes six months to 3 years, depending on the state. However, in California, GoPuff tried to acquire BevMo! which is helpful for them to scale.

New York City is full of people, but with so many different grocery “dark stores” and convenience to other retail food stores, consumers are constantly taking advantage of promotions, low prices, and free items. These companies are burning money as part of their promotion. The biggest challenge faced by rapid grocery delivery companies is covering the costs of their operation and expansion. Infrastructure such as vertically integrated supply chain planning and analytics platform that includes AI and machine learning become of enormous importance in determining the long-term existence and growth of grocery “dark stores” by focusing on more efficient supply chain management and customer acquisition process. In general, e-commerce and quick commerce platforms such as Amazon and all other online retail deliveries platform got a massive tailwind from COVID-19 restrictions. People were looking for options to get their needs delivered. However, an industry expert during the industry interview mentioned that in the future, the grocery store would evolve to be built with packing and operation areas that people cannot see anymore. With their current business model and real estate prices keep increasing, grocery “dark stores” provide a leaner inventory profile with a smaller footprint that is able to save real estate costs and limit the complexity of the store layout and where things are. In the short run, some of these companies, such as Gorillas and GoPuff, have also started to allow customers to walk in and browse for items to comply with city regulations.

Takeaways

The demand for quick and convenient grocery delivery has been amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has contributed to the optimism surrounding these services, However, the sustainability of the grocery “dark stores” business model is yet to be determined. The growth of these services can be influenced by factors such as customer satisfaction, operational efficiency, and market competition. To determine the sustainability of grocery “dark stores” it will be necessary to monitor how these services evolve, adapt to market condition, and address challenges such as profitability, customer loyalty, and market consolidation. The unit economics and long-term viability of the grocery “dark stores” model will need to be evaluated over time to determine its sustainability and potential in cities and on the industry.

From the findings, I found that changes to the number of grocery “dark stores” establishments per NTA vary from 33% to 100%. Their exits were influenced by the consolidation of the ultrafast delivery sector in the country as the space faced dwindling investor funding, a competitive economic environment, and political influence. For example, in an article by Grocery Dive, JOKR CEO, and cofounder Ralf Wenzel mentioned that the company decided to leave the United States to focus its resources on Latin America because the region is still underpenetrated and underserved. In addition, Fridge No More and BUYK shut down from the US market due to US Sanctions on Russia, as Russian investors backed both startups (Garber, 2022).

On average, grocery “dark stores” that survived the following year, although not significant, had higher potential in coming in the year 2022 and closer demographic characteristics than the general average (Table 15 and 16). In addition, the surviving stores had more extensive funding from Venture Capitalists: billions versus millions. Moreover, a surviving company such as GoPuff has been around in the United States since 2013, steadily progressing and expanding its operations and technology platform. GoPuff CEO Yakir Gola mentioned that it is indeed a complex business to scale; for example, to expand their service line to include alcohol, the process takes six months to 3 years, depending on the state. However, in California, GoPuff tried to acquire BevMo! which is helpful for them to scale.

New York City is full of people, but with so many different grocery “dark stores” and convenience to other retail food stores, consumers are constantly taking advantage of promotions, low prices, and free items. These companies are burning money as part of their promotion. The biggest challenge faced by rapid grocery delivery companies is covering the costs of their operation and expansion. Infrastructure such as vertically integrated supply chain planning and analytics platform that includes AI and machine learning become of enormous importance in determining the long-term existence and growth of grocery “dark stores” by focusing on more efficient supply chain management and customer acquisition process. In general, e-commerce and quick commerce platforms such as Amazon and all other online retail deliveries platform got a massive tailwind from COVID-19 restrictions. People were looking for options to get their needs delivered. However, an industry expert during the industry interview mentioned that in the future, the grocery store would evolve to be built with packing and operation areas that people cannot see anymore. With their current business model and real estate prices keep increasing, grocery “dark stores” provide a leaner inventory profile with a smaller footprint that is able to save real estate costs and limit the complexity of the store layout and where things are. In the short run, some of these companies, such as Gorillas and GoPuff, have also started to allow customers to walk in and browse for items to comply with city regulations.

Takeaways

The demand for quick and convenient grocery delivery has been amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has contributed to the optimism surrounding these services, However, the sustainability of the grocery “dark stores” business model is yet to be determined. The growth of these services can be influenced by factors such as customer satisfaction, operational efficiency, and market competition. To determine the sustainability of grocery “dark stores” it will be necessary to monitor how these services evolve, adapt to market condition, and address challenges such as profitability, customer loyalty, and market consolidation. The unit economics and long-term viability of the grocery “dark stores” model will need to be evaluated over time to determine its sustainability and potential in cities and on the industry.

Takeaways for New York City

The emergence of grocery “dark stores” in contrast to the generally favorable reception of MFCs and online delivery services, has sparked a sense of concerns among many. Early on, there was a prevailing concern that dark stores were eliminating retail opportunities, particularly as they began to proliferate. During an interview, Frank Ruchala, the Director of Zoning at the New York City Department of City Planning mentioned that it is worth noting what occupied these spaces before the advent of grocery “dark stores”. Many of these locations had been vacant for extended periods, adding to the existing challenge of retail vacancies in the city. The question arises: Is this a problem in itself, or does it reflect a larger issue within the city? Despite the initial apprehension surrounding dark stores, Frank mentioned that in New York City, specifically Manhattan, this situation never escalated to a critical point where clear conclusions could be drawn.

However, the proliferation of grocery “dark stores” has inspired New York City to look at why and how this is happening and to think about the long-term future. Over the course of several decades, zoning regulations have played a significant role in addressing various issues related to retail spaces. In the 1960s and 1970s, concerns arose about the dominance of banks, which seemed to occupy every available retail location. In response to that, zoning measures were implemented to regulate the distribution and concentration of banks. Subsequently, in the 1990s and 2000s, the presence of banks and travel agencies in urban areas decreased significantly leading to a shift in the retail landscape. During this time, pharmacies became prominent occupants of retail spaces. The history of retail spaces reflect the constant evolution of new trends and changes. People have deep attachment to these spaces, as they contribute to neighborhood experience, and there is concern that alterations in retail establishments could impact their overall community experience.

Frank Ruchala mentioned that the grocery “dark store” debate and the issues surrounding it have provided the city with valuable insights and lessons, prompting them to consider the long-term future through the lens of planning. With skyrocketing rents, the global transformation of retail, and the ever-changing economic landscape, it becomes crucial to update and revise the existing rules to better reflect the dynamic nature of the city. As planners, Frank said, we need to contemplate the future of these companies and their place in our urban environment. Additionally, the city face the challenge of determining when quick grocery delivery is the preferable option. Nevertheless, it is essential to consider the type of goods that are not typically sold in local store such as bodegas and to consider how the city and businesses can cater to those who are home bound, such as older people and individuals with disabilities. While the concept of grocery “dark store” may have its drawbacks, city planners must still explore ways to serve and meet the needs of those who are unable to access traditional stores within a short walking distance.

The emergence of grocery “dark stores” in contrast to the generally favorable reception of MFCs and online delivery services, has sparked a sense of concerns among many. Early on, there was a prevailing concern that dark stores were eliminating retail opportunities, particularly as they began to proliferate. During an interview, Frank Ruchala, the Director of Zoning at the New York City Department of City Planning mentioned that it is worth noting what occupied these spaces before the advent of grocery “dark stores”. Many of these locations had been vacant for extended periods, adding to the existing challenge of retail vacancies in the city. The question arises: Is this a problem in itself, or does it reflect a larger issue within the city? Despite the initial apprehension surrounding dark stores, Frank mentioned that in New York City, specifically Manhattan, this situation never escalated to a critical point where clear conclusions could be drawn.

However, the proliferation of grocery “dark stores” has inspired New York City to look at why and how this is happening and to think about the long-term future. Over the course of several decades, zoning regulations have played a significant role in addressing various issues related to retail spaces. In the 1960s and 1970s, concerns arose about the dominance of banks, which seemed to occupy every available retail location. In response to that, zoning measures were implemented to regulate the distribution and concentration of banks. Subsequently, in the 1990s and 2000s, the presence of banks and travel agencies in urban areas decreased significantly leading to a shift in the retail landscape. During this time, pharmacies became prominent occupants of retail spaces. The history of retail spaces reflect the constant evolution of new trends and changes. People have deep attachment to these spaces, as they contribute to neighborhood experience, and there is concern that alterations in retail establishments could impact their overall community experience.

Frank Ruchala mentioned that the grocery “dark store” debate and the issues surrounding it have provided the city with valuable insights and lessons, prompting them to consider the long-term future through the lens of planning. With skyrocketing rents, the global transformation of retail, and the ever-changing economic landscape, it becomes crucial to update and revise the existing rules to better reflect the dynamic nature of the city. As planners, Frank said, we need to contemplate the future of these companies and their place in our urban environment. Additionally, the city face the challenge of determining when quick grocery delivery is the preferable option. Nevertheless, it is essential to consider the type of goods that are not typically sold in local store such as bodegas and to consider how the city and businesses can cater to those who are home bound, such as older people and individuals with disabilities. While the concept of grocery “dark store” may have its drawbacks, city planners must still explore ways to serve and meet the needs of those who are unable to access traditional stores within a short walking distance.

Takeaways for Other Cities

Despite years of attention on platform urbanism: from Uber to Alipay, from Airbnb to Deliveroo, cities have not been fully able to mitigate the impact of these grocery “dark stores” present. The potential reshaping of private-public power geometries in the wake of platform urbanism is a crucial and emergent issue: new urban platforms can serve as an interface not just between tech firms, governments, and citizens (Caprotti et al., 2022). These platforms serve more broadly as interfaces between how the relationship between private and public sectors is articulated and managed.

It is an important aspect to consider the relationship between specific cities and the growth of technology that promote platforms with urban impact. For a city, these issues are intricately linked not only to power dynamics between local authorities and specific urban areas but also to how to navigate diverse regulatory and policy environments, as these platforms often operate across different ones. Platform urbanism has given rise to problems, in part because social processes have been extracted from traditional regulatory frameworks that are often constrained nationally (Nash et al., 2017). Many governments are now grappling with platform-focused questions such as how to limit the oversupply of grocery “dark stores” in the city or how to ensure that the presence of grocery “dark stores” does not kill the economy of local grocery stores such as Bodega and delicatessen in Manhattan. However, some platform providers, in this case grocery “dark stores” are beginning to engage with regulatory processes as a means of gaining market access, political approval, and exploiting potentially lucrative niches. Grocery “dark stores” are starting to comply with considering opening their access for walk-ins and online pick-ups.

Cities need to consider the implications of different types of platforms and the specific geometry of their constituent actors in the digital era. There is a need for digital urban policy and regulation to comply with how platforms can reshape the nexus between businesses, cities, and citizens. While it is helpful to anticipate what can go wrong, it is even more critical to get in front of the trends to harness the benefit of the tech-enabled digital economy and urban ecosystem. As this thesis project exhibits, in the era of the internet era and platform urbanism, regulation does not necessarily mean following regulations according to existing rules and standards or enforcement through traditional institutions. Suppose society is to benefit from the opportunities provided by platform innovation. In that case, regulation must not be driven by the vested interests of those industries or institutions with the most to lose but rather by new assessments of what constitutes the public good (Nash et al., 2017). Cities and technology continue to evolve, and we need to ask whether there are alternatives to existing ways of organizing disruption in cities through platform urbanism.

Despite years of attention on platform urbanism: from Uber to Alipay, from Airbnb to Deliveroo, cities have not been fully able to mitigate the impact of these grocery “dark stores” present. The potential reshaping of private-public power geometries in the wake of platform urbanism is a crucial and emergent issue: new urban platforms can serve as an interface not just between tech firms, governments, and citizens (Caprotti et al., 2022). These platforms serve more broadly as interfaces between how the relationship between private and public sectors is articulated and managed.

It is an important aspect to consider the relationship between specific cities and the growth of technology that promote platforms with urban impact. For a city, these issues are intricately linked not only to power dynamics between local authorities and specific urban areas but also to how to navigate diverse regulatory and policy environments, as these platforms often operate across different ones. Platform urbanism has given rise to problems, in part because social processes have been extracted from traditional regulatory frameworks that are often constrained nationally (Nash et al., 2017). Many governments are now grappling with platform-focused questions such as how to limit the oversupply of grocery “dark stores” in the city or how to ensure that the presence of grocery “dark stores” does not kill the economy of local grocery stores such as Bodega and delicatessen in Manhattan. However, some platform providers, in this case grocery “dark stores” are beginning to engage with regulatory processes as a means of gaining market access, political approval, and exploiting potentially lucrative niches. Grocery “dark stores” are starting to comply with considering opening their access for walk-ins and online pick-ups.

Cities need to consider the implications of different types of platforms and the specific geometry of their constituent actors in the digital era. There is a need for digital urban policy and regulation to comply with how platforms can reshape the nexus between businesses, cities, and citizens. While it is helpful to anticipate what can go wrong, it is even more critical to get in front of the trends to harness the benefit of the tech-enabled digital economy and urban ecosystem. As this thesis project exhibits, in the era of the internet era and platform urbanism, regulation does not necessarily mean following regulations according to existing rules and standards or enforcement through traditional institutions. Suppose society is to benefit from the opportunities provided by platform innovation. In that case, regulation must not be driven by the vested interests of those industries or institutions with the most to lose but rather by new assessments of what constitutes the public good (Nash et al., 2017). Cities and technology continue to evolve, and we need to ask whether there are alternatives to existing ways of organizing disruption in cities through platform urbanism.

©juanitahalim 2025